Unit One: Character Foundations

This unit contains four lessons and one worksheet. Work through the content in order.

Revelations are the key moments throughout your story when the hero discovers, learns, and/or realizes something that greatly influences their subsequent actions/choices. When thoughtfully planned and plotted, revelations are the key to a well-executed character arc, driving the story toward an immensely satisfying conclusion.

What does a revelation look like in fiction?

A revelation is a powerful moment of inner clarity for the hero. ‘Moment’ might even be a stretch. Revelations often happen in a matter of seconds, like a lightbulb going off in the hero’s head. As such, these instances can be cinematic, shocking, and/or moving—for both the hero and the reader.

Revelations—these beats that happen internally for the hero—are the key to fleshing out character arcs. Think of revelations as the zipper that pulls your A Story and B Story together; the melding of a literal journey and an emotional journey.

Don’t confuse reveals with revelations. The words sound similar, and though they are closely intertwined, for the course of this workshop, they will accomplish different things.

Reveals happen externally, in the story world, at a plot level. Revelations happen internally, for the hero, in their head.

Every good scene will reveal something, be it new crucial information (eg: the main suspect has an alibi) , or a new obstacle/conflict (eg: the hero had become the main suspect). The bigger the reveal, the more likely it will trigger a revelation for your hero.

Now, when I say “big”, I don’t mean that the reveal has to be a massive, earth-shattering plot twist that pulls the rug from beneath the reader’s feet, though that can work nicely in some instances. By “big,” I simply mean that the reveal is impactful enough to change the course of the plot; the character is forced to pivot and adapt because of this reveal.

An example: A detective might learn that the main suspect wasn’t at work the night of the murder. This information reveal isn’t going to trigger a revelation for the protagonist. It’s going to lead the detective to dig farther, attempting to confirm that the suspect was at the scene of the crime. But a later interview with a hospital employee could reveal that the main suspect was in the ER due to a medical emergency the night of the murder. The main suspect is entirely innocent. A reveal of this magnitude forces the detective back to the drawing board. How do they proceed from here? It is in moments like this, where the hero must regroup, pivot, and adapt, that revelations are likely to occur.

If reveals happen at a plot level, revelations happen at a character level, and when implemented correctly, they’ll help take a story from merely entertaining to truly exceptional.

Take a moment to think of one of your favorite stories—book, movie, tv. The medium doesn’t matter. Got a story in your head? Good. Now identify a revelation—an “ah-ha!” moment—that occurred for the hero and helped them go on to succeed in their goals.

Did you come up with one? Great. Did it by any chance occur in the third act?

If yes, you likely identified this revelation because third act revelations are often the most memorable. Why? The beat usually hits after a whopper of a reveal, often a big plot twist. Examples:

How the hero reacts to this reveal—the revelation that they have in response to it—is often key to completing their character arc. If the revelation you identified during this exercise occurred at an earlier point in the story, have no fear! Revelations in the first and second acts are just as crucial to writing a satisfying and nuanced arc.

In this workshop, we will take a deep dive into your story’s plot, determining what makes your hero tick, how other characters challenge and influence them, and the key revelations that will help your hero not only succeed, but complete an emotional journey in the process. When you’ve finished working your way through the material, you will have a blueprint of where to place your revelations so that your plot is efficient, effective, and entertaining.

In short, revelations…

Before we can dig too deeply into your story’s revelations, we have to step back and look at your hero. Which brings me to the phrase “Character drives plot.”

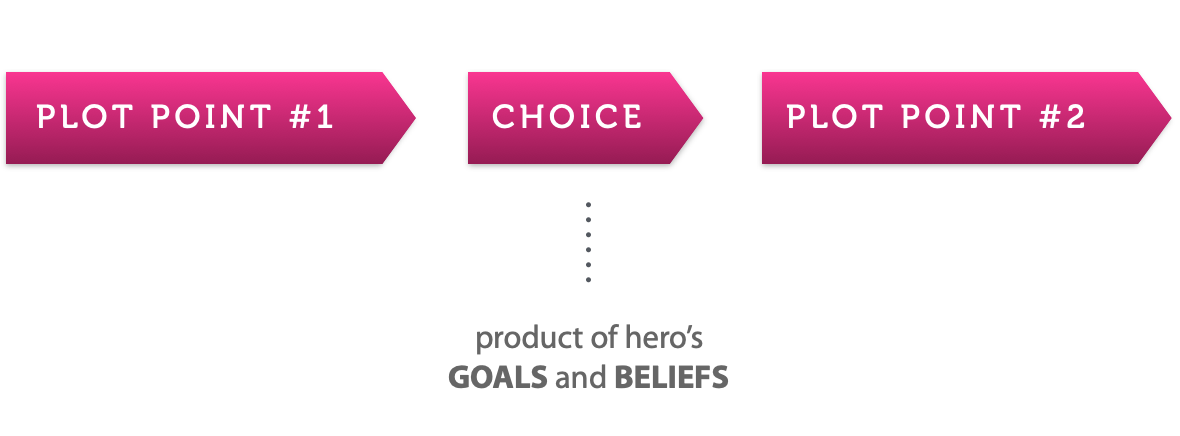

You’ve probably heard this statement before—and for good reason. The plot should never push the character along, forcing them down a certain path. Instead, the character’s choices should propel the plot. Always. Their decisions (which they come to as a result of their goals and beliefs) will dictate what happens next.

When a reader comments that a character’s actions felt forced, or that they were acting “out of character,” this is usually a sign that the writer forced the character to make choices that would benefit the plot they envisioned, rather than letting the character’s belief system and goals inform their decisions and, in turn, direct the narrative.

Earlier I mentioned the No Man’s Land scene from Wonder Woman (2017). If you haven’t seen it before, you can watch it here. The viewer knows how risky it is to attempt to cross this stretch of land because Steve Trevor tells Diana bluntly that doing so is impossible. Still, Diana tries to cross it. And guess what? This decision feels completely natural and authentic to her character.

Why? Well, in the first act of the movie we get a glimpse of the things that Diana believes. In short, that humankind is good and worth saving—that every life has value. We also see that while she is powerful, she is naive and trusting, sometimes to a fault. Her core beliefs and her inner faults combine to make this decision to march into No Man’s land the only decision. Of course she does it.

The decision also aligns with her goals—the thing she wants to accomplish most over the course of the story—which is to end the war. Diana can only accomplish this larger goal by getting to the front (on the other side of No Man’s Land). The most direct route is through this area and she can help more people and save more lives in the process. This scenario creates a perfect little trifecta of belief/goal/decision tension that allows Diana’s actions to feel 100% in character.

Successfully plotting your revelations requires you to know who your character is, inside and out—specifically what they believe about themselves, their larger world, and the way a person should live within it.

Before we can plan and plot our revelations, we need to understand what the hero wants. What is he/she trying to accomplish over the course of the story? What are they fighting with the villain over? This is their want/goal and it should influence every decision they make.

In The Hunger Games, Katniss’s initial goal is to provide for and protect her family. Later her goal is to survive the Games, which is really just an evolution of her initial goal. Survival is a strong motivator, but for Katniss it is also necessary if she wants to continue to keep her family safe.

The belief system is the foundation of a good character arc. No matter what your character believes or stands for, when your story begins, the hero must be wrong about something. There must be a fatal flaw in their thinking or worldview. This belief must be so flawed that it is actively hurting them (and maybe even those around them.) Worse still, this belief is keeping them from succeeding in their goal.

This flawed worldview is often referred to as the character’s “lie.” In fact, K.M. Weiland calls this “the lie your character believes.” Giving your character a lie (or several) sets you up for massive potential character growth.

In The Hunger Games, Katniss believes several lies at the start of the novel:

When lies are listed out bluntly like this, it is almost always easy to recognize how flawed they are. The key to making them palatable to the reader is to ensure that the lies make sense within the context of the story world.

How does this shake out in The Hunger Games? Well, after the death of her father, Katniss watched her mother fall apart, and so she’s come to believe that loving makes you weak and that staying closed off from others keeps you stronger and safer. Watching her mother deteriorate also taught Katniss that that no one was coming to save her. If she didn’t want her family to starve, there was no better person to count on than herself. She started hunting in the woods and assumed the role of “mother” within the household. Lastly, Katniss lives in an oppressive world of poverty and limited resources. She knows how important every scrap of bread is. But Peeta gave her family bread once when she was younger, and to be in his debt—or anyone’s—puts her own family at risk.

While we can recognize that Katniss’s beliefs are flawed, we can easily understand how she came to accept this worldview. Characters, after all, are a product of their world.

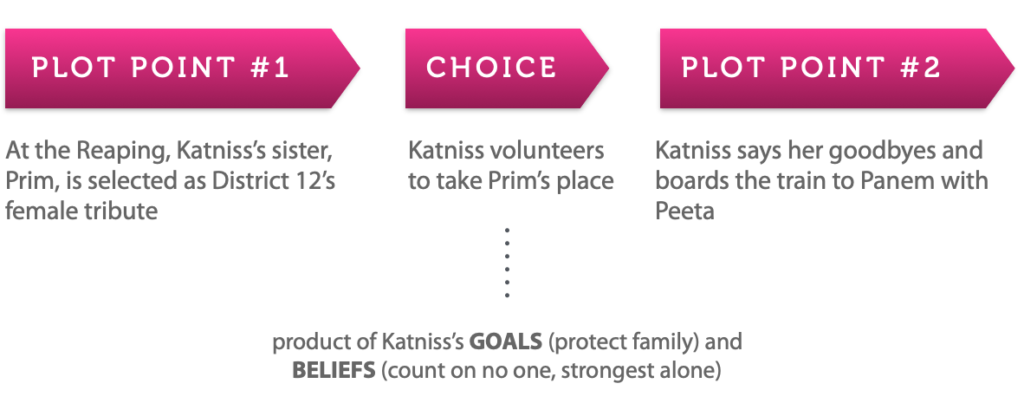

The hero’s goal and belief system will influence every single decision they make—including the revelations they eventually have. Let’s look closer at the inciting incident of The Hunger Games.

Katniss’s decision to volunteer in her sister’s place is a direct product of her goals (protect her family at all cost) and her beliefs (in this case, the lie that she should count on no one but herself).

The choice to volunteer as tribute shifts Katniss’s end goal slightly (new goal: survive the Games), but at this point in time she doesn’t have a revelation. She doubles down on her belief that she doesn’t need help. In fact, it would be foolish to expect anyone to fix things for her. Katniss can—and will—do this alone.

In stories where the hero’s belief system includes multiple lies, it is important to identify the thematic lie—the lie that hints at what the story is all about. While books shouldn’t aim to solely teach a lesson, you, the author, are trying to say something. (If you’re not, why are you writing this book?) The biggest lie that the hero needs to reject will often align with this “message.”

For example, in Vengeance Road, my heroine Kate believes several lies, but her thematic lie is the belief that justice is the only thing that can bring you peace. Kate’s other lies make it even more difficult for her to see her flawed thinking in regards to the thematic lie. The other lies must break/fall first in order for her to eventually accept that justice by any means necessary is not the way to find peace. In fact, the pursuit of justice at all costs can corrupt you in the process.

Other examples of thematic lies:

Woody can only experience growth when he realizes it’s not about being the favorite toy but about being someone’s toy, period. Winnie can only grow when she understands that a life lived forever is a blessing and a curse. Will can only grow when he acknowledges that there may be other ways to be loyal to your family besides avenging a murder with more murder.

A quick note: Keep in mind that the thematic lie doesn’t have to be in direct contrast of your book’s theme. Vengeance Road has several themes, one of which works with Kate’s thematic lie. Another is that “gold makes monsters of men” as Kate’s father warns. As you consider your hero’s lies, the lie that is the thematic lie is the one that says the most about who you want your hero to become. It is the biggest life-altering view change they will have.

As a story unfolds, obstacles (plot) should always challenge your hero to reject their lie(s). The closer the hero gets to accomplishing their goal, the less they will be able to defend their flawed worldview.

This is true with The Hunger Games as well. Katniss’s entire experience in the Arena forces her to confront the belief system she lived by when the book began. By the end of the novel, she’s rejected the lie that she is strongest alone. Instead, she knows that she is stronger with Peeta, that united they stand a chance not only of surviving, but of sending a message to the Capitol.

The final revelation of your novel should be the last puzzle piece, the final ah-ha! moment that allows the hero to reject their lie(s) completely and experience growth. This moment should occur in the third act, either just before the final battle or even during it.

Mad Max: Fury Road is a fantastic example of well-executed final revelations. Because it has two main characters (Furiosa and Max) it also delivers multiple complete character arcs by way of these revelations, packing twice the punch.

Max and Furiosa have similar goals in the movie—part of the reason they become such fitting allies. They both want to escape the tyrannical rule of Imorten Joe. Furiosa, more specifically, wants herself and the other women (wives) to be free of his exploits. Max wants to escape, period.

Their lies are similar as well, but a bit more nuanced:

So how does the final revelation play out? Let’s break it down…

Remember in the very first lesson when I mentioned that big reveals often trigger revelations? This is true in Fury Road. A good old fashioned plot twist propels us into the final act (and to the revelations that allows the heroes to complete their arcs.)

The reveal that the Green Place is gone (it was actually the swampy bog they already passed through) hits Furiosa and the viewer in the gut. This twist also triggers a change in goal. Furiosa needs to find a new paradise. She sets out in search of a new home despite knowing there is nothing but wasteland for miles.

As the characters scramble to adapt in the face of the reveal, their new plans can trigger revelations. This is true in Fury Road. After parting ways with Furiosa, Max has an idea. He races after her and proposes that paradise is actually where they started. If they ride hard, they can return to the Citadel while it is unguarded and take control of it.

This new plan triggers the movie’s final revelations (or at least, Furiosa’s).

In this moment, she realizes that Max is right. His plan is the only way she can truly escape Imorten Joe and secure a future worth living. She shakes hands with Max—agreeing to his plan, accepting his help. She rejects the lie that no one can be trust anyone, completing her character arc. United, Furiosa and Max race for the Citadel and the final battle kicks off. Note that this final revelation comes a bit early, but it feels balanced because Max’s revelation hits later.

For Max, simply proposing the new plan is a step toward him rejecting his lie, but his true revelation comes several scenes later, after the final battle, when he gives Furiosa a blood transfusion and tells her his name. In this moment, he rejects his lies that he can’t grow close to anyone and that life can only be one animalistic survival action after the next. Instead, he embraces his humanity and chooses to believe in hope—and in others.

These final revelations (one for each hero) complete two different character arcs. The viewer is then left with a final image: Furiosa and Max parting ways as equals, respectful of each other. This is a long cry from the distrustful enemies they were when they first met.

They are irrevocably changed by their journey (which is the goal of any successfully executed character arc) and revelations helped them get there.

The final revelation in the third act of your story is often the moment you hero reject their lies and completes their character arc. What about the earlier acts? Shouldn’t they have revelations, too? Yes. And this leads us into the next unit: Pacing Revelations.

It’s time to break down your hero’s goal and belief system. As you work through the sheet, I’ll be providing examples using my YA historical fiction western, Vengeance Road.

A quick note: If your story has more than one hero/narrator, you may want to work through the sheet for each. That said, try to identify the most central or overarching voice and start with that hero, as their goals/system will be the driving force for the novel.

For example: My sci-fi horror novel Contagion has multiple narrators, but I would say that the novel is Althea’s story first and foremost. As such, I’d start these worksheets with her in mind. In Retribution Rails, I have dual narrators of equal page time and importance, but I would work through these sheets with Reece as my primary hero, as the entire conflict of the novel stems from actions taken by his character in the opening chapter.

Download Unit One Worksheet

In this video, I answer popular questions that come up during Unit One. It is best watched after reading through all the lessons.

*NOTE: There are no longer live FAQ zoom calls. For new questions, you can email me or submit them here and I’ll answer them on the Discord.

If you have technical issues or need to reach me directly, please send an email.